As used by Mr Mouse for the keys to the Magic Kingdom...

Monday, 30 May 2011

Monday, 23 May 2011

Friday, 20 May 2011

THE PUPPET'S PROGRESS

My recent post on the naming of Jiminy Cricket has prompted me to write about what is, pretty much, my all-time favourite Disney film...

...which is why I was so delighted, back in 2009, to get the opportunity to officially enthuse for the No Strings Attached, 'Making of...' feature on the 70th Anniversary DVD release of the film. And, indeed, here I am, caught on a screen-grab, in mid-gab...

I recently watched Pinocchio again (although, over the years, I must have seen it close on sixty times) and having now seen it yet one more time – in that last sparkling restoration filled with the richest colours and deepest shadows – I'm even more certain that this film is not just one of the great masterpieces of animation but also a great movie in any genre.

I first saw Pinocchio from the front row of the circle in the Odeon, Bromley, Kent, sometime in the early ‘sixties, when it was already on its umpty-umpth re-release. So entranced was I that I went back to see it again and again - and again!

This, of course, was in the days of 'continuous performances' which meant that I was able to watch Pinocchio no fewer than eight times in one week!

Teaching myself to write in the dark, I filled an entire notebook with minute observations about the animation, the structure of the storytelling, the set-pieces and effects and the incredible richness of detailing such as Geppetto's incredible array of carved clocks (above) that create an intense - almost claustrophobic - atmosphere of fantastical reality that swallows up the viewer as surely as Monstro the Whale has swallowed up Geppetto's boat.

The painting above (and the one below), by the Swedish artist, Gustav Tenggren, are two of many pieces of inspirational art which helped create the ornately sumptuous styling of the film that is, essentially, a European picture book come to life.

Pinocchio was released in 1940, just two years after Disney's first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and the picture undoubtedly benefited not just from all the lessons learned in animating Snow White, but also from the fact that the huge financial success of that debut outing made it possible for serious money to be spent on developing the studio's second feature. The refinement of craft and increased expenditure can be seen in almost every sequence of Pinocchio.

Nevertheless, he two films could scarcely be more different: the first has freshness, exuberance and a naïve innocence that no Disney feature would ever re-capture; the second is more a more mature and studied piece of film-making, bolder and braver in breaking with the sweet formula of the fairy tale and in creating a cast of characters, a number of whom have an ambiguous morality.

Like the book, the film is a picaresque tale in which Pinocchio's journey (similar in didactic tone to that of Christian in John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress) is fraught with disturbing encounters, difficult choices and painful self-discoveries.

Then there is the tone and look of the film. Despite the occasional scary moments Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is essentially a light, airy film, whereas Pinocchio is dark and sombre…

It runs for just under an hour and a half and yet less than 15 minutes of that time takes place in daylight: the rest is made up of sinister night sequences and scenes shot underwater and within the gloomy, vaulted, cathedral-like interior of the whale.

There are scenes of menace and sheer out-and-out terror: Pinocchio cowering in a cage as Stromboli the puppet-master tells him that he will make a lot of money and when he is no longer any good he will make excellent firewood - a warning which he demonstrates by hurling a hatchet into the body of a lifeless puppet lying in a basket of wood...

Or, again, the scene in the dingy, smoky interior of the Red Lobster Inn where the Coachman reveals his scheme for abducting naughty little boys and taking them to Pleasure Island, his fat, flabby face transforming into a leering demon that terrifies even the crooked Honest John.

Above all, there is the shocking moment when the tough-kid, Lampwick, begins to transform into a donkey: running amok in the pool hall, kicking over chairs and tables and smashing mirrors with his newly-developed hooves.

True, at the end of the film there is a happy ending for Pinocchio, but not for Lampwick or for the other donkey-boys who have been crated up and sent to the salt mines.

A number of sequences carry a terrible sense of desolation: the ruins of Pleasure Island after the boys have reeked havoc and destruction; and the dusty interior of Geppetto’s deserted workshop after he has gone off to look for his missing boy.

Magically, the film juggles the terrifying with the funny, the harsh with the sentimental. And the forces of malevolence, whilst being an ever-present threat, are always counterpointed by the constancy of Geppetto and the loyalty of the temperamental but big-hearted Jiminy Cricket, who begins the film as a storyteller but then steps into the story itself not just as Pinocchio's conscience but also as the audience's guide and companion.

When Geppetto wishes on the Wishing Star that Pinocchio might become a real boy, Jiminy observes: “A really lovely thought but not all practical…” And when the Blue Fairy does, indeed, endow the puppet with life, he says with genuine astonishment, “What they can’t do these days!”

The Jiminy device (unique to the film since – as I mentioned in my last post – Carlo Collodi, originally had Pinocchio flatten the Talking Cricket with one of Geppetto's mallets!) gives immediacy to the tale so that it appears to be a first hand recollection, a true story that really happened.

We ought to wonder about the oddness of it all - a sharp-talking, street-wise, American commentator who looks hardly anything like a real cricket and basically is only a cricket because we are told that he's a cricket. But we accept it entirely at face value despite the fact that this spunky little insect-man is providing a commentary on a story that unfolds in a quaint, old-fashioned European world that is less like Collodi's Italy than somewhere on the borders of Switzerland and Germany.

The use of the Multiplane camera, that had been employed only sparingly in Snow White, gives Pinocchio great depth as can be seen in the opening pan across the moonlit rooftops and the spectacularly elaborate sequence of the hustle and bustle of the village coming awake to the sound of the school bell: the camera moves among the knotted jumble of streets and squares to reveal children running, laughing and playing at the pump; a mother giving a child's face a final scrub; an old man smoking his pipe; a baker going on his rounds; a goose girl driving her geese...

The animators also made skillful use of visual perspectives as in the shot filmed from Jiminy’s point of view as the camera - along with the cricket - literally hops towards the lighted window of Geppetto's workshop.

As for the special effects, they proliferate and are stunning: fire, smoke, lightning and rain; the Blue Fairy's magic wand; the distorted view of Pinocchio through Cleo’s goldfish bowl; Jiminy floating down on his umbrella reflected on the convex surface of Monstro’s eyeball; and the extraordinary sea scenes: the waves, wind and foam, the uproar of surf churned up by the enraged Monstro and the picturesque underwater landscape filled with reflections, bubbles and swirling shoals of fish...

Pinocchio is a tour de force of economic storytelling: compressing the many exploits in Collodi’s book into a single, compelling narrative, told in part through the music and songs that help delineate character and advance the plot: the fraudulent Honest John's 'Hi-diddly-dee, an Actor's Life for Me'; Pinocchio's 'There Are No Strings On Me', an ironic song of freedom sung just before his imprisonment by Stromboli; and Jiminy Cricket's 'Give a Little Whistle' and the opening and closing ballad, 'When You Wish Upon a Star' (movingly rendered by Jiminy's voice, Cliff Edwards) which became - and remains - the anthem of the Disney studio.

At the end of the film, Pinocchio the puppet becomes a real boy and whilst he is nowhere near as appealing as he was as Geppetto's "little wooden-head", the old woodcarver, along with Figaro and Cleo, seems very happy about the transformation.

I, too, am content, since every time I watch Pinocchio, I am transported back to the front row of the circle in the Odeon, Bromley, and also become (albeit briefly) a real boy once more...

...which is why I was so delighted, back in 2009, to get the opportunity to officially enthuse for the No Strings Attached, 'Making of...' feature on the 70th Anniversary DVD release of the film. And, indeed, here I am, caught on a screen-grab, in mid-gab...

I recently watched Pinocchio again (although, over the years, I must have seen it close on sixty times) and having now seen it yet one more time – in that last sparkling restoration filled with the richest colours and deepest shadows – I'm even more certain that this film is not just one of the great masterpieces of animation but also a great movie in any genre.

I first saw Pinocchio from the front row of the circle in the Odeon, Bromley, Kent, sometime in the early ‘sixties, when it was already on its umpty-umpth re-release. So entranced was I that I went back to see it again and again - and again!

This, of course, was in the days of 'continuous performances' which meant that I was able to watch Pinocchio no fewer than eight times in one week!

Teaching myself to write in the dark, I filled an entire notebook with minute observations about the animation, the structure of the storytelling, the set-pieces and effects and the incredible richness of detailing such as Geppetto's incredible array of carved clocks (above) that create an intense - almost claustrophobic - atmosphere of fantastical reality that swallows up the viewer as surely as Monstro the Whale has swallowed up Geppetto's boat.

The painting above (and the one below), by the Swedish artist, Gustav Tenggren, are two of many pieces of inspirational art which helped create the ornately sumptuous styling of the film that is, essentially, a European picture book come to life.

Pinocchio was released in 1940, just two years after Disney's first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and the picture undoubtedly benefited not just from all the lessons learned in animating Snow White, but also from the fact that the huge financial success of that debut outing made it possible for serious money to be spent on developing the studio's second feature. The refinement of craft and increased expenditure can be seen in almost every sequence of Pinocchio.

Nevertheless, he two films could scarcely be more different: the first has freshness, exuberance and a naïve innocence that no Disney feature would ever re-capture; the second is more a more mature and studied piece of film-making, bolder and braver in breaking with the sweet formula of the fairy tale and in creating a cast of characters, a number of whom have an ambiguous morality.

Like the book, the film is a picaresque tale in which Pinocchio's journey (similar in didactic tone to that of Christian in John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress) is fraught with disturbing encounters, difficult choices and painful self-discoveries.

Then there is the tone and look of the film. Despite the occasional scary moments Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is essentially a light, airy film, whereas Pinocchio is dark and sombre…

It runs for just under an hour and a half and yet less than 15 minutes of that time takes place in daylight: the rest is made up of sinister night sequences and scenes shot underwater and within the gloomy, vaulted, cathedral-like interior of the whale.

There are scenes of menace and sheer out-and-out terror: Pinocchio cowering in a cage as Stromboli the puppet-master tells him that he will make a lot of money and when he is no longer any good he will make excellent firewood - a warning which he demonstrates by hurling a hatchet into the body of a lifeless puppet lying in a basket of wood...

Or, again, the scene in the dingy, smoky interior of the Red Lobster Inn where the Coachman reveals his scheme for abducting naughty little boys and taking them to Pleasure Island, his fat, flabby face transforming into a leering demon that terrifies even the crooked Honest John.

Above all, there is the shocking moment when the tough-kid, Lampwick, begins to transform into a donkey: running amok in the pool hall, kicking over chairs and tables and smashing mirrors with his newly-developed hooves.

True, at the end of the film there is a happy ending for Pinocchio, but not for Lampwick or for the other donkey-boys who have been crated up and sent to the salt mines.

A number of sequences carry a terrible sense of desolation: the ruins of Pleasure Island after the boys have reeked havoc and destruction; and the dusty interior of Geppetto’s deserted workshop after he has gone off to look for his missing boy.

Magically, the film juggles the terrifying with the funny, the harsh with the sentimental. And the forces of malevolence, whilst being an ever-present threat, are always counterpointed by the constancy of Geppetto and the loyalty of the temperamental but big-hearted Jiminy Cricket, who begins the film as a storyteller but then steps into the story itself not just as Pinocchio's conscience but also as the audience's guide and companion.

When Geppetto wishes on the Wishing Star that Pinocchio might become a real boy, Jiminy observes: “A really lovely thought but not all practical…” And when the Blue Fairy does, indeed, endow the puppet with life, he says with genuine astonishment, “What they can’t do these days!”

The Jiminy device (unique to the film since – as I mentioned in my last post – Carlo Collodi, originally had Pinocchio flatten the Talking Cricket with one of Geppetto's mallets!) gives immediacy to the tale so that it appears to be a first hand recollection, a true story that really happened.

We ought to wonder about the oddness of it all - a sharp-talking, street-wise, American commentator who looks hardly anything like a real cricket and basically is only a cricket because we are told that he's a cricket. But we accept it entirely at face value despite the fact that this spunky little insect-man is providing a commentary on a story that unfolds in a quaint, old-fashioned European world that is less like Collodi's Italy than somewhere on the borders of Switzerland and Germany.

The use of the Multiplane camera, that had been employed only sparingly in Snow White, gives Pinocchio great depth as can be seen in the opening pan across the moonlit rooftops and the spectacularly elaborate sequence of the hustle and bustle of the village coming awake to the sound of the school bell: the camera moves among the knotted jumble of streets and squares to reveal children running, laughing and playing at the pump; a mother giving a child's face a final scrub; an old man smoking his pipe; a baker going on his rounds; a goose girl driving her geese...

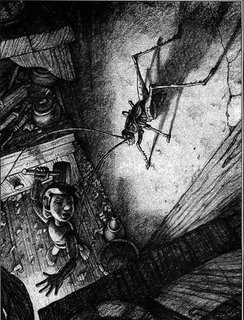

The animators also made skillful use of visual perspectives as in the shot filmed from Jiminy’s point of view as the camera - along with the cricket - literally hops towards the lighted window of Geppetto's workshop.

As for the special effects, they proliferate and are stunning: fire, smoke, lightning and rain; the Blue Fairy's magic wand; the distorted view of Pinocchio through Cleo’s goldfish bowl; Jiminy floating down on his umbrella reflected on the convex surface of Monstro’s eyeball; and the extraordinary sea scenes: the waves, wind and foam, the uproar of surf churned up by the enraged Monstro and the picturesque underwater landscape filled with reflections, bubbles and swirling shoals of fish...

Pinocchio is a tour de force of economic storytelling: compressing the many exploits in Collodi’s book into a single, compelling narrative, told in part through the music and songs that help delineate character and advance the plot: the fraudulent Honest John's 'Hi-diddly-dee, an Actor's Life for Me'; Pinocchio's 'There Are No Strings On Me', an ironic song of freedom sung just before his imprisonment by Stromboli; and Jiminy Cricket's 'Give a Little Whistle' and the opening and closing ballad, 'When You Wish Upon a Star' (movingly rendered by Jiminy's voice, Cliff Edwards) which became - and remains - the anthem of the Disney studio.

At the end of the film, Pinocchio the puppet becomes a real boy and whilst he is nowhere near as appealing as he was as Geppetto's "little wooden-head", the old woodcarver, along with Figaro and Cleo, seems very happy about the transformation.

I, too, am content, since every time I watch Pinocchio, I am transported back to the front row of the circle in the Odeon, Bromley, and also become (albeit briefly) a real boy once more...

Monday, 16 May 2011

MICKEY MONDAYS: Weekly Manifestations of the Mouse

A Mickey pen from Disneyland Paris – for keeping notes on your sorcery experiments!

Thursday, 12 May 2011

"CRICKET'S THE NAME!"

"What is your name?"

"Oh, Cricket's the name. Jiminy Cricket."

"Oh, Cricket's the name. Jiminy Cricket."

One of the inevitable facts about famous books becoming famous movies is that, sometimes, it can be difficult to remember what was in the original and what was added or adapted during the process of Hollywoodisation.

Several Disney films could serve as a case in point: ask anyone to name the Seven Dwarfs and they would manage at least four or five; and yet, those little men had no names in any version of the fairy-tale uncle Uncle Walt retold it in 1937.

Similarly, the 1940 film, Pinocchio, reminds me that the name of the puppet's 'Official Conscience', Jiminy Cricket, has its own curious history...

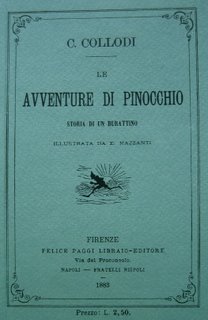

Similarly, the 1940 film, Pinocchio, reminds me that the name of the puppet's 'Official Conscience', Jiminy Cricket, has its own curious history...When, in 1883, writer 'Carlo Collodi' (real name Carlo Lorenzini) began writing Le Avventure di Pinocchio for an Italian children's newsparer he included a brief encounter between the marionette and a Talking Cricket who, in those days, still didn't have a name.

Pinocchio tells the Cricket that his ambition in life is to "eat, drink, sleep and amuse myself, and to lead a vagabond life from morning to night," and this prompts an outburst of weighty moralising by the Cricket who informs the puppet that: "As a rule, all those who follow that trade end almost always either in a hospital or in prison." This, in turn, leads to an exchange with an extremely ugly outcome...

"Take care, you wicked, ill-omened croaker! Woe to you if I fly into a passion!"

"Take care, you wicked, ill-omened croaker! Woe to you if I fly into a passion!""Poor Pinocchio! I really pity you!"

"Why do you pity me?"

"Because you are a puppet and, what is worse, because you have a wooden head."

At these last words, Pinocchio jumped up in a rage and, snatching a wooden hammer from the bench, he threw it at the Talking-Cricket.

Perhaps he never meant to hit him, but unfortunately it struck him exactly on the head, so that the poor Cricket had scarcely breath to cry "Cri-cri-cri!" and then he remained dried up and flattened against the wall.

Later in the story, the Cricket's ghost comes back from the dead to do some more sermonising, but Walt Disney decided to keep the Cricket alive and to continue his spirited attempts at guiding Pinoke on “the straight and narrow path” throughout the movie.

Obviously, such a major character required a name… But the moniker 'Jiminy Cricket' wasn't Disney's invention; it was borrowed from an already everyday expression - dating back to 1848 - denoting puzzlement or surprise: “JIMINY CRICKETS!”

But, why Jiminy Crickets? Well, if you look at the initials of that name -- J. C. -- there's your answer…

Jiminy Crickets (or sometimes Jiminy Christmas) is a euphemistic alternative to swearing by the person whom the British writer and raconteur, Quentin Crisp, used to refer to as "Mister Nazareth"!

It seems likely that the origin of the expression was overlooked by Disney who had already allowed it to be used by the dwarfs in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (made three years before Pinocchio) when, on returning from their diamond mine, they discover that their home has been invaded by a princess with a penchant for cooking and cleaning!

Jiminy Crickets is an example of what is called a 'minced oath' - a kind of profanity chosen by those who would rather "mince their words", than risk giving offence…

Jiminy Crickets is an example of what is called a 'minced oath' - a kind of profanity chosen by those who would rather "mince their words", than risk giving offence…So, instead of saying J**** C*****, you say Cheese and Rice, Jeepers Creepers, Jason Crisp, Judas Priest --- or good old Jiminy Crickets!

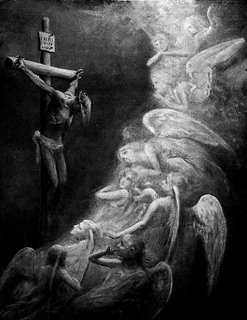

Other examples of 'minced oaths' include such Shakespearian expletives as 'Zounds', short for 'God's wounds' referring to the crucifixion, and 'Gadzooks', from 'God's hooks', or the nails in the cross.

Other examples of 'minced oaths' include such Shakespearian expletives as 'Zounds', short for 'God's wounds' referring to the crucifixion, and 'Gadzooks', from 'God's hooks', or the nails in the cross.By golly!, By gosh! and By gum! are all handy ways of NOT saying By GOD! And By Jove! is useful if you normally address the deity as Jehovah but want to avoid outright blasphemy.

On the other hand, the commonly used Drat! is a seriously shortened version of God rot it! which actually has a good deal more oomph to it and, in my opinion, really deserves to be reinstated into the language.

It should also be noted that Figs! and Fink! - should you happen to hear them used - are alternatives to the ubiquitous 'F' word - though, I'd guess, pretty much obsolete nowadays…

So, there you are: a bit of movie history and a lesson in etymology all in one!

Godfrey Daniels! What more could you ask?

[Image of Pinocchio and the Cricket by Greg Hildebrandt on Spiderwebart; the Crucifixion is by Dore]

A version of this post first appeared on Brian Sibley: his blog in 2006.

Tuesday, 10 May 2011

WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

For a great shot of a fantastic

stained-glass window

in Le Château de la Belle au Bois

(Sleeping Beauty's Castle)

in Disneyland Paris,

along with links to a couple of others

(like the one on the left)

visit my companion blog

Window Gazing.

Saturday, 7 May 2011

DISNEYLAND HISTORY UNFOLDS

A Disneyland souvenir from the '60s – this one was posted to the UK in 1966.

It is fascinating to think just how much has changed (and, in particular, how permanent some things look in these pictures that are long, long gone!) but also how much has remained exactly the same!

Looking at the "26 colorful scenes" on this concertina post-card, I find myself really wishing I'd seen Nature's Wonderland and had a go on the Flying Saucers. Never mind, I did see the original Fantasyland (before its 1983 face-lift) and had lunch on Captain Hook's Pirate Galleon!

It is fascinating to think just how much has changed (and, in particular, how permanent some things look in these pictures that are long, long gone!) but also how much has remained exactly the same!

Looking at the "26 colorful scenes" on this concertina post-card, I find myself really wishing I'd seen Nature's Wonderland and had a go on the Flying Saucers. Never mind, I did see the original Fantasyland (before its 1983 face-lift) and had lunch on Captain Hook's Pirate Galleon!

Monday, 2 May 2011

BARKING UP THE WRONG TREE

Going under the hammer at O'Gallerie, Portland, Oregon, today at 7:00pm PST:

"Lot 180: An original Walt Disney watercolor and gouache on celluloid from the 1955 movie, The Lady and the Tramp (sic).

"Depicts Tramp seated beside a small fox on a tree stump."

Er... No! Not quite...

But good to know that Toughy and Pedro eventually escaped from that ghastly City Pound. Let's hope that Peg and the others were similarly lucky!

"Lot 180: An original Walt Disney watercolor and gouache on celluloid from the 1955 movie, The Lady and the Tramp (sic).

"Depicts Tramp seated beside a small fox on a tree stump."

Er... No! Not quite...

But good to know that Toughy and Pedro eventually escaped from that ghastly City Pound. Let's hope that Peg and the others were similarly lucky!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)